A Day Aboard the Neeskay

This July, I had the pleasure of joining a small group of teen interns, scientists, and podcasters onboard the research vessel Neeskay. As a lover of maritime history, open water, and Moby Dick, it was something of a wish-fulfillment for me. Like the infamous Captain Ahab and his motley crew, we were in search of an elusive quarry we couldn’t see or hear, an underwater target whose position we could only surmise. In our case, in place of a raging white whale, we sought out something that originated a bit farther afield: visitors from outer space.

I’d been invited to join the Aquarius Project on another hunt for meteorites at the bottom of Lake Michigan. Around nine AM, we arrived in Manitowoc, Wisconsin—myself, Chris Breskey (Teen Programs Manager at the Adler), three teen interns (Jack, Mike, and Liz), and a few others, including an audio engineer for the ongoing Aquarius Project Podcast. Before we unmoored, we all were tasked with the unexpected challenge of wriggling in and out of full-body immersion suits that must have weighed thirty pounds and felt more like straight-jackets than floatation devices. The Neeskay’s venerable captain Greg was kind enough to help me zip mine up when it became clear that my arms were unlikely to move.

Once successful, we set out across the waves under a crystal blue sky, the morning sun already blazing and the breeze gently coaxing us out of the harbor and into the deep.

As you may know, Adler teens are searching for fragments of a meteor that streaked across the sky in early 2017 and exploded somewhere off the coast of Lake Michigan. Scientists and teens have since narrowed down the likeliest path of entry for the extraterrestrial fragments and are using a magnetic sled, designed specifically for this mission, to search the murky depths for small rocks from elsewhere in our solar system.

It takes a while to get from shore to the designated tow zone. Built in 1953, 71 feet long and displacing sixty-two and a half tons, the Neeskay is a sturdy old boat with a long history of scientific contribution—but she isn’t known for her speed. That, coupled with the fact that each lowering of the magnetic sled takes around an hour to complete, meant that there was a lot of downtime. The teens kept busy making adjustments to equipment, analyzing samples, programming sensors, and sifting through mud. I, on the other hand, had little to do but swat flies.

So, in the tradition of my beloved 19th Century mariners who whiled away the summer days on the lazy seas of the Atlantic doldrums, I sat around, talked to the teens while they worked, observed, and drew little pictures—my own personal scrimshaw.

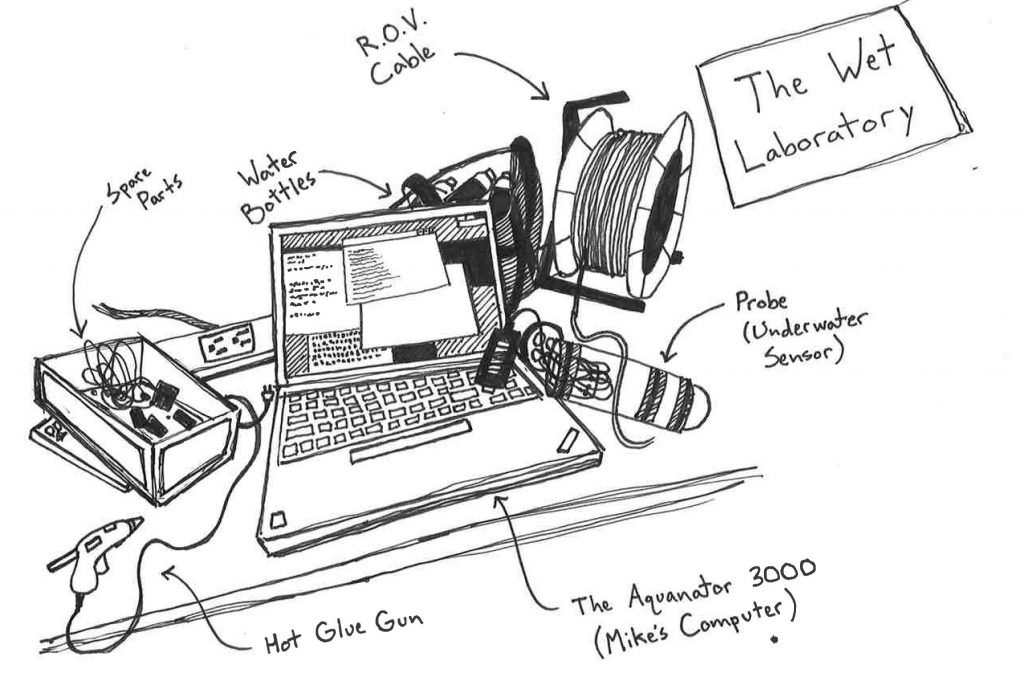

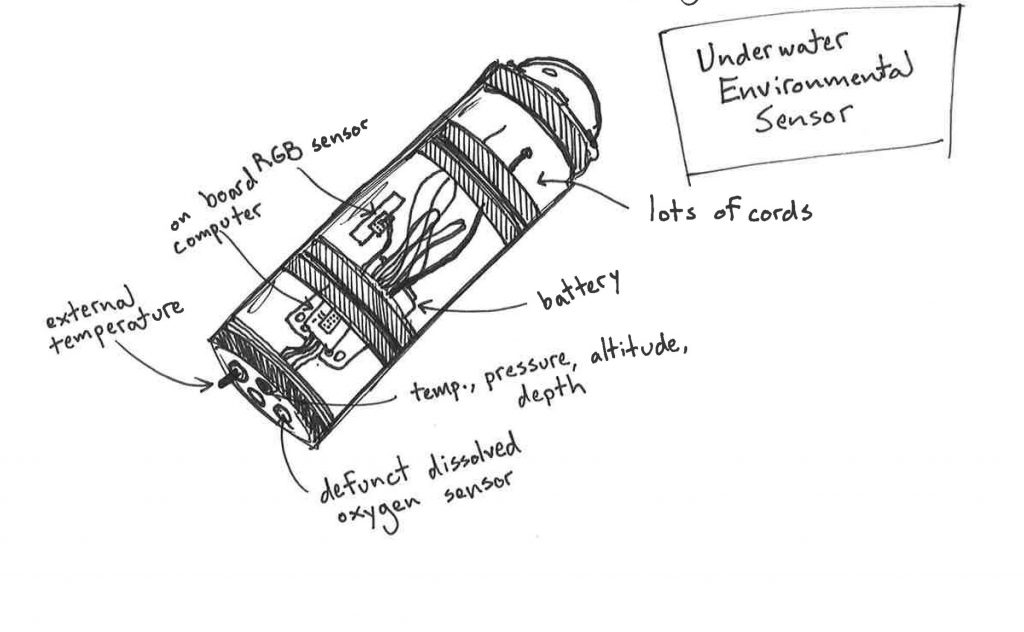

Here, for example, I wanted to capture a snapshot of the cluttered organization that was the “Wet Laboratory,” a space below the top deck, behind the captain’s bridge, where we watched a live video feed from the sled as it dragged across the lakebed. It was also the room where I sat with Mike, one of the three Far Horizons teens interns I met that day, and learned about the underwater sensor he was programming. As we talked, the boat engine rumbled below deck, small fans whirred above, and Mike demonstrated how the sensors recorded second-by-second data on external temperature, pressure, altitude, and depth. Here’s a closer look:

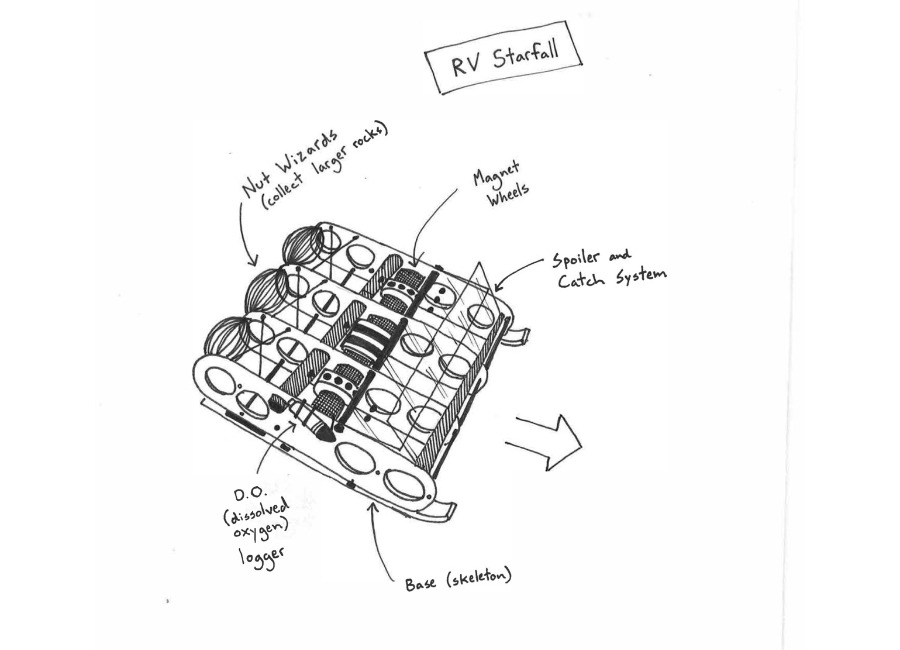

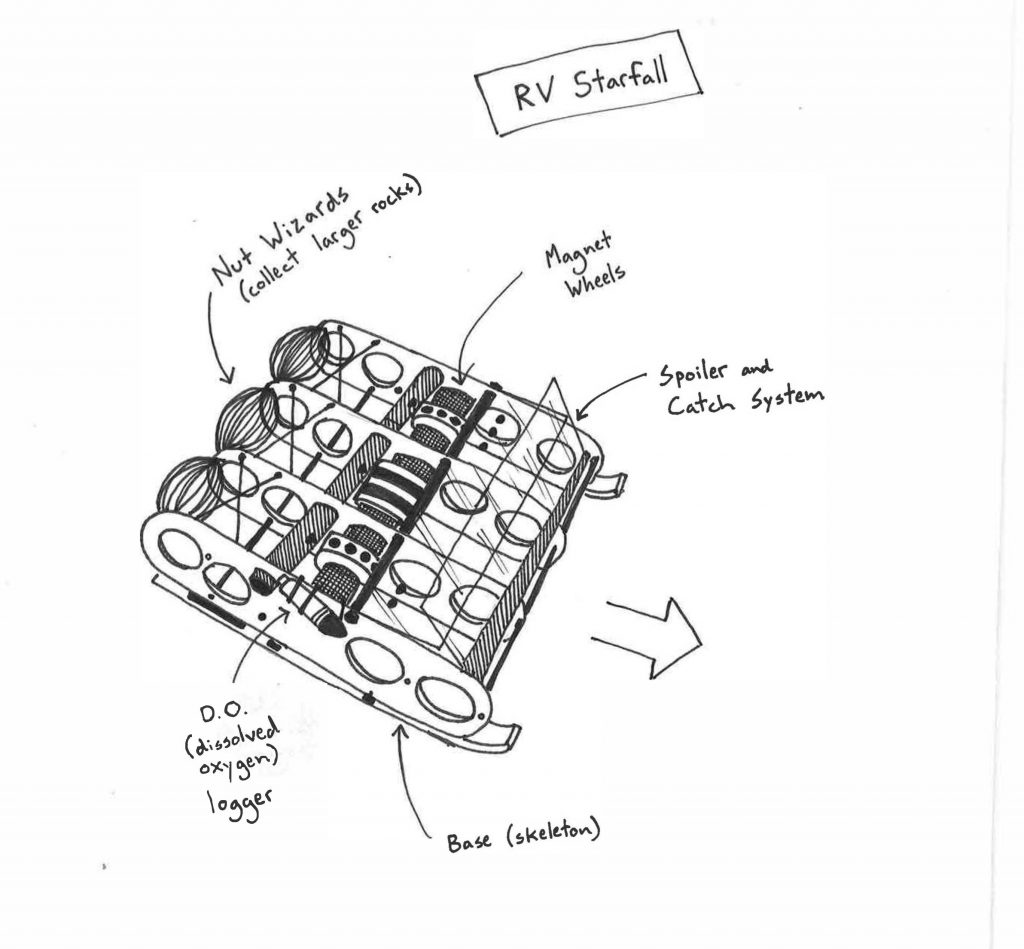

To collect useful data, the teens attached their underwater sensor to the key piece of equipment that makes the whole Aquarius mission possible: a submersible sled designed by teens and affectionately dubbed Starfall. A complex mash-up of magnetic wheels, spoilers, sensors, and “nut wizards” (a technical term—they were originally designed to capture acorns, balls, and other yard debris strewn throughout a messy lawn), Starfall is the workhorse of the Aquarius Project.

Several times throughout our voyage I watched from the decks as the crew lowered the Starfall beneath the waves and waved goodbye as it slipped into the dark. 85 meters down, it settled onto the lakebed, coaxing up a cloud of mud and quagga mussels on our computer screens that took a moment to clear up. When the dust had settled, an alien landscape appeared in the ghostly light of the ROV camera. Hundreds of feet below, under forty-six fathoms of water, muffled by darkness and pressures that would kill a human without specialized diving gear, the Starfall crawled along, with the hopes of Adler teens resting on its steel and PVC shoulders.

After about an hour trawling along the bottom at the Neeskay’s minimum speed, the mechanical pulley system dragged the probe back up from the depths. Then ensued a mad dash to collect any rocks the sled succeeded in sifting from the muck. I was happy to witness for myself the distinct magnetic action of a few of these finds, and while their origin (terrestrial or otherwise) hasn’t been verified as of the writing of this report, it was thrilling to see how a few little rocks can still capture the imagination and signify so much to us Earthlings.

I want to thank the Aquarius team for welcoming me on its expedition this summer. It was a voyage I won’t soon forget. The conversations, the science, the horizons and the waves—even the biting flies. When I looked out and listened to the water, stretching out for miles in every direction, I thought about the amazing fluke of coincidence that brought a visitor from outer space right here to a little stretch of lake we call Michigan, a reminder that the Universe isn’t so far away after all.

You, too, can follow along on this crazy journey by tuning into the Aquarius Project Podcast (available on iTunes, Soundcloud, Stitcher—or wherever you get your podcasts!). Hear the voices of Adler teens for yourself and take part in a once-in-a-lifetime mission to bring our meteorite back to light!

Sketches and drawings by Jonathan Russell.