Encouraging STEM Education in Underrepresented Groups: An Interview with Dr. Ellen Ochoa

By Brenda Galan, former teen intern in the Collections Department through the Smithsonian’s Latino Center Young Ambassadors Program. In her spare time, you can find her writing poetry, watching food and travel shows on Netflix, cooking, and trying to learn a new language on Duolingo!

Header Image: Dr. Ellen Ochoa floating upside down on the Shuttle. Credit: NASA

Early exposure to STEM education is becoming a crucial and prevalent part of today’s rapidly changing world; however, for many, this is a daunting field due to rigorous coursework and a lack of support for underrepresented communities. As a first-generation college student and Latina, this is something that resonates with me on a personal level.

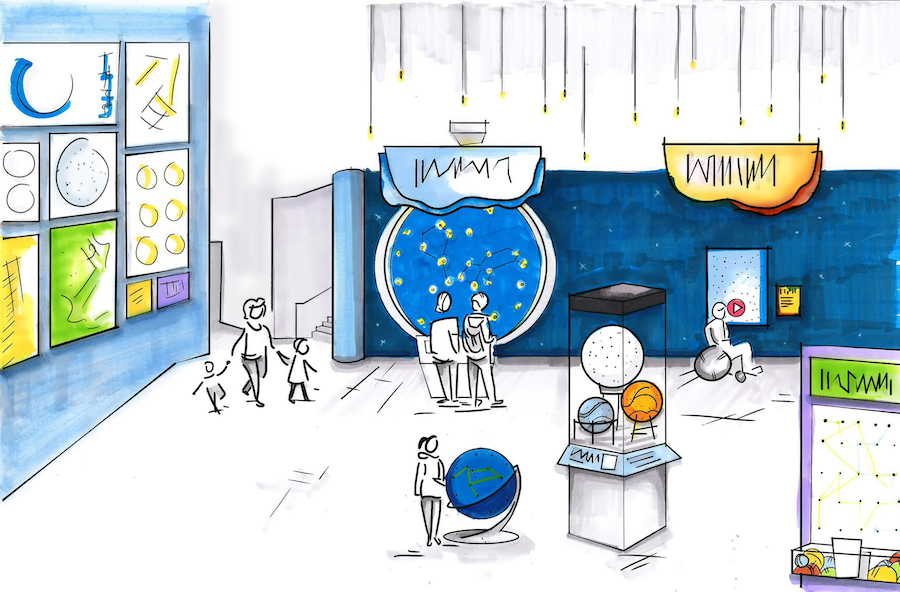

During my time at the Adler Planetarium, I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Ellen Ochoa—the first Latina to ever fly to space—about her journey pursuing a degree in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Who was your biggest inspiration when you were younger?

I think the person that had the biggest influence on me, particularly when I was younger, was my mother. She valued education very highly. I think it was because she thought it’d lead to a life where you could have a good job and interesting challenges, but also she loved learning. She was just always interested in lots of different things. When I was growing up, she was raising five kids and didn’t have the opportunity to go to college, but she was taking one college class a semester while I was growing up. She graduated from college two years after I did, but for a long time, she just took [classes] because she was interested in learning more. I think all of my brothers, sisters, and I saw that and viewed learning as one of the most interesting things you could do.

Who or what prompted you to pursue a career in a STEM field?

It took me a while to figure that out, but the main way I got into it was through my math classes. When I got to college, even though originally I was thinking of majoring in music or business, I took calculus. I started to explore other subjects and by the time I was finishing up the calculus series, I started looking at subjects that use math. I ended up talking to a couple of professors at San Diego State University and to a professor in the electrical engineering department to find out more about that subject. I didn’t know anything about engineering or science at that point and, unfortunately, he wasn’t very welcoming. I then talked to a professor in the physics department and got quite a different reception. He talked about things you could do with physics. I honestly didn’t know what things you could do with a physics degree. He asked me what kind of math I had taken and I told him I was finishing up the calculus series and he said, “You’ll be way ahead if you’ve already taken calculus… I think you’d do really well.” So, I think it’s not too surprising that I decided to give physics a try.

Have you dealt with stereotypes about women in STEM? If so, how do you tackle that in the workplace?

It’s there, but I would say it’s improved in the time that I’ve been, not only at graduate school, but in the workforce. Over the last decades, it’s improved a lot, but it’s still there and it’s maybe not as obvious; you don’t always know when you’re facing it. One thing I would say is, hard work and perseverance always help and it doesn’t matter what your background is. Sometimes it falls on you to help remove those stereotypes, unfortunately, by showing that you can do the work. In some cases, it’s been helpful to show that those stereotypes are outdated and don’t make any sense anymore. That can be a difficult thing, particularly at the beginning of a career, when you’re just trying to show that you can do the work. As my career progressed, and I got into positions of management and leadership, I had the opportunity as Director of Johnson Space Center, to work on the culture and environment there. I helped increase not only the diversity, but strived to provide an atmosphere that was inclusive and supportive.

Did you ever experience imposter syndrome as it pertains to women or minorities? What advice would you give to other people who are experiencing imposter syndrome?

When I was younger, I often wondered, “Do I have what it takes?” at every step of the way when I was doing something that I hadn’t done before. What makes it worse is when you look around and don’t see anybody like yourself, then you really wonder. It’s something that a lot of people feel, and it’s not restricted to women or minorities. When I first declared physics as a major, I was glad the professor had encouraged me because I kept thinking, “I never took physics in high school and everybody in this class knows more than I do.” It took a long time and different ways of validating it. I’d get the highest grade in the class and would think, “I need to not psych myself out because I can actually do the work.”

When I first joined the astronaut corps, I had made it through a pretty rigorous selection process, which should have given me a fair amount of confidence. Learning to land under a parachute, being picked up out of the water by a Coast Guard helicopter, flying in a high-performance aircraft were all things I had no background in. Whereas people who had been selected from the military were very familiar with that. On the other hand, a lot of the training was like school; we had lectures and stacks of workbooks that we had to read through. I could make notes and study, so that was something I was familiar with after ten years of college.

I tried to look at it as, “I can do well on things I’m familiar with.” As for the things I wasn’t familiar with… We had trainers and other members of my astronaut class where the idea was, “We want you to succeed, we’re helping you learn this stuff because if you’re going to do well as an astronaut, this is part of it.” It’s taking one step at a time and saying, “I’ve managed to learn a lot of new things in my life and this is just one more new thing.”

What do you say to first-generation college students who are interested in pursuing a STEM education?

The first thing I say is we need you, we need your brain. So I want to encourage them to do so. There are different paths you can pursue with a STEM background, and I think the world is becoming a place where different kinds of fields use some kind of science or engineering in their field. Having that background gives you many more options although, not seeing many people like us in that field can sometimes discourage people. I was often in classes, in both undergrad and graduate school, where I was the only woman and the only person of Hispanic background. That gets a little bit tiring, to be honest, but I think there’s a lot that people can take advantage of. Almost everybody will have trouble in one class and find it difficult, and if you don’t see anybody like yourself, you can get the erroneous impression that you’re the only one going through that. A lot of universities now have student chapters of organizations like the Society of Women Engineers or the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers. These are places where you can see other people like you, form study groups, find resources, and get encouragement.

In thinking about the future what is your biggest hope for women of color who want to pursue a degree in STEM?

I hope that a lot more will choose to do so and that they’ll be welcomed into those fields. The numbers are still pretty discouraging although they’re higher in some areas of STEM than others. In biology, biomedical engineering, and some of the social sciences, the numbers have gotten better for women overall and a little bit better for underrepresented minorities. Unfortunately, in some of the areas like electrical or mechanical engineering, and computer science, the numbers haven’t been growing as much. There’s actually a few more women in computer science now than there used to be, so I would hope that we attract more women in those areas. I think part of it is understanding, particularly on the engineering side, that engineering is about solving problems. These can be problems that both women and underrepresented minorities care about because they affect people they know and love. It’s about curiosity, creativity, and working in teams; though engineering is not always portrayed that way. Sometimes talking about it in a different way helps to encourage and attract underrepresented minorities who haven’t chosen those fields in very large numbers yet.

How has your narrative helped you shape the person that you are today?

It’s always hard to separate how one thing affected it more than any other. I had people that discouraged me, but I also had people who encouraged me along the way. Most of those people were men because that was who my professors were, and who my supervisors were when I worked; I actually never had a woman supervisor. Different kind of people can serve as mentors, sponsors, or as people who help you out, so I certainly saw that; people gave me opportunities as I entered the work field. Both my Ph.D. advisor and associate advisor were men who’ve always been supportive, and I’m still in contact with them, thirty-five years later!

I don’t think it’s true that only people who look like you can serve as mentors and that’s actually good news, because you may not see that many people like you as you go through. Yet I certainly benefited from advice and opportunities that people provided me. So, if you find you are either working for or taking classes with someone who isn’t very supportive, “take steps to look around for people who will be supportive because they’re out there.” It may take a little bit more work to find them but those are the kinds of people that you want to talk to and get advice from.

What has been the biggest highlight in your career?

It’s a hard question to answer because I’m so fortunate; of course, to have had the opportunity to fly in space and be part of a team that’s trying to accomplish something whether it’s a new scientific discovery or building the international space station. Other than that, I would say the opportunity to talk to lots of students, particularly girls, and underrepresented minorities has been a highlight. You probably know I have six schools named after me and I’ve been at the dedication of each one. So, getting to talk to the students there but also very dedicated teachers and staff has been something I never really could’ve imagined but has been really rewarding.

Do you have any advice for me as an incoming college freshman?

First of all, I think you have a great start in getting to do this great internship; it’s quite an opportunity that I think will help as you start in school. Realize that “Okay, you know I’m gonna work hard but it’s not gonna be any harder for me than for other students here.” If you run into difficulties understanding something in a class, make sure you take advantage of what’s out there, to help you whether it’s the professor’s office hours, or getting together with student chapters and organizations.

Interviewing Dr. Ellen Ochoa has been impactful and something I never could have imagined. Because STEM careers are prevailing in today’s world, and often aren’t pursued by people of color, my initial feelings about it were unnerving.

As someone from an underrepresented group, speaking to Dr. Ochoa, a woman pioneer, left me optimistic about my future. I knew that for her to overcome adversity and succeed in her field meant that other underrepresented minorities could too. Not only was the conversation empowering, but it shifted my perspective a lot in thinking about engineering. It’s extremely crucial that other minorities hear the stories of those same people who’ve faced adversity and have overcome it. Often times, as college students from underrepresented backgrounds, we face much distress; a common form of distress for us can be imposter syndrome. When you are reminded of others who’ve helped pave the way for both minorities and women, though, it results in the empowerment of those seeking to attain a career in those fields.