A Conveyance to This Other World

LUNAR MOUNTAINS AND VALLEYS

In November 1609, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) set out to study the Moon using a recent invention he had heard about a few months prior, and had been playing with ever since: the telescope. According to the principles of Aristotelian cosmology, which still prevailed at the time, the celestial bodies (including the Sun, the Moon, the planets, and the fixed stars) revolved around a central and static Earth, attached to crystalline spheres. They were all supposed to be pristine and unchangeable. However, what Galileo saw with a 20-powered telescope made by him when he pointed it at the Moon was not an immaculate orb. It was rather a world with surface features that, according to Galileo, looked like the mountains and valleys on Earth. Galileo was not the first to observe our satellite through a telescope, but he caused a stir when he published his findings in a short illustrated book titled Sidereus Nuncius (“The Starry Messenger,” or “The Starry Message”) in March 1610. It was also in this book that Galileo announced his discovery that Jupiter has satellites. All of this seemed to contradict the old ideas about the cosmos that had prevailed for almost two thousand years. After all, the Moon was a place just like the Earth, and that was likely the case with the planets as well. And if those are all actual places, then we should in principle be able to go there.

THE MAN IN THE MOONE

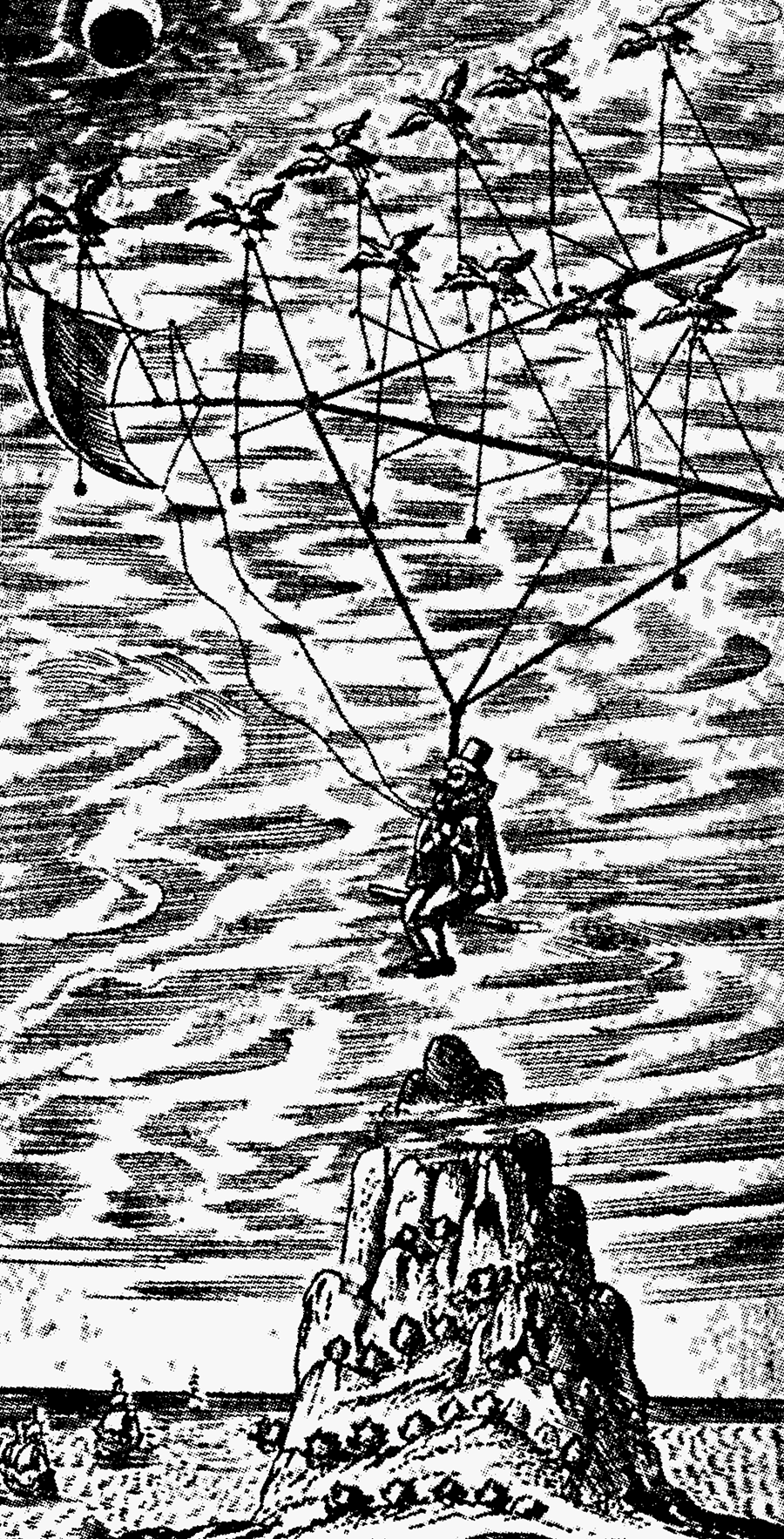

Galileo’s telescopic discoveries played an important role in the debates around the idea developed by Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) decades earlier—that the Earth is but a planet orbiting a central Sun along with the other planets. Scholars and writers who similarly to Galileo embraced the Copernican system were enthused by the new telescopic findings. Some set out to imagine what it would be like to travel to the other worlds that make up the Solar System, and the Moon was an obvious first destination. Around 1608, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), known for the laws of planetary motion with his name, wrote novel titled Somnium (“The Dream”), in which he describes imaginary trips to the Moon with the aid of spirits and where he also speculates about the appearance of the Earth and celestial phenomena as observed from the Moon. Somnium was published posthumously in 1634, by the initiative of Kepler’s son. Four years later, another fictional work containing reveries about space travel was published: Francis Godwin’s The Man in The Moone. Here a character named Domingo Gonsales (who is also presented as the author of the book) travels to our satellite pulled by a flock of robust birds called “gansas”. This may not sound much better than spirits, but Godwin had nonetheless taken a step further by addressing a fundamental issue: what kind of physical means could release us from the Earth’s gravitational attraction (which would be much better understood a few decades later with the works of Isaac Newton) and potentially take us to our satellite.

“A CONVEYANCE TO THIS OTHER WORLD”

While Kepler, Godwin, and other 17th-century writers used fiction to muse about lunar journeys, John Wilkins (1614-1672) took the subject more seriously. Wilkins was a mechanical-minded clergyman who also supported the Copernican system. He played an important role in the establishment of the Royal Society of London, a key institution for the emergence of modern science. In 1638 (the same year of The Man in the Moone), Wilkins published The Discovery of a World in the Moone, an essay where he discusses the habitability of our satellite and analyzes possible ways of travelling there. He would expand on these ideas in a subsequent edition of the essay and in another book titled Mathematical Magick (1648). Wilkins analyzed four ways of travelling to the Moon: with the aid of spirits or birds (as in the fictional works of Kepler and Godwin); with artificial wings; and finally, by riding a vehicle he called the Flying Chariot. The latter would be propelled either directly by its passengers, or by clockwork springs. It was Wilkins’s favorite option. Summarizing the ideas presented in The Discovery…, he wrote that, “it may be possible for some of our posterity to find out a conveyance to this other world; and if there be inhabitants there, have commerce with them.” At least regarding the first part, Wilkins was certainly right—it just took three centuries of social and technological change, the appropriate spacecraft (or types of flying chariots and propulsion if you will), and above all, the same daring imagination to approach the subject that he and his aforementioned contemporaries had.