Defying Boundaries in the Museum World

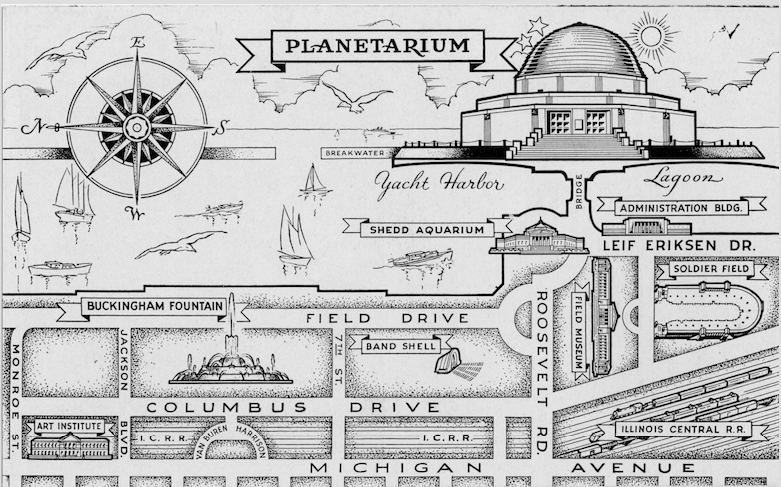

The Adler Planetarium opened to the public on May 12, 1930, forming a triumvirate of museums with the Field Museum and the Shedd Aquarium in what is nowadays known as Chicago Museum Campus, a beautiful park by Lake Michigan. In 1932 the Adler’s first director, Philip Fox, wrote: “the three [museums] are fittingly closely associated and form a trinity dedicated to the study of ‘The Heavens above, the Earth beneath, and the waters under the Earth’”. Fox was paraphrasing a biblical passage (Exodus 20:4) in order to emphasize that these institutions not only complemented each other, as together they were virtually able to cover nature in its entirety.

Regardless of their affinities and shared location, each of the three institutions would essentially follow its own path over the ensuing decades. There is nothing unusual or surprising about that. In the nineteenth century, the pursuit of knowledge, in the humanities as in the physical and natural sciences, was increasingly marked by the division of each major field of inquiry into disciplines and sub-disciplines. This movement was concomitant with the rise of the professional scientist, the emergence of the research university, and the development of the public museum as an informal place of learning. Museums were inevitably shaped by this drive towards fine-grained disciplinarity, with each institution seeking to define its own identity and scope. In many cases, the same museum came to host disparate curatorial cultures with little or no communication between them.

Of

Aquarius thus brings to full fruition Fox’s vision for the Adler Planetarium in the context of Chicago Museum Campus. It likely goes beyond what Fox had in mind when he wrote the passage cited above, as he was probably thinking less of collaboration between the three museums and more about their combined potential to attract public by being physically close to each other.

The Aquarius Project may or may lead to meteorite fragments in the bottom of Lake Michigan, but besides all it has accomplished already as a collaborative and educational endeavor, it also offers plenty of food for thought as to what museums (be them museums of science, art, or another subject) may accomplish by reaching out to their neighbors and fellow institutions.

Header Image: Postcard from the 1930s featuring the Adler Planetarium in what is nowadays known as Chicago Museum Campus. Note the Shedd Aquarium just below, and Field Museum next to it. (Adler Planetarium Archives).