Former Adler intern aims to clean up air travel with ‘impossible’ tech

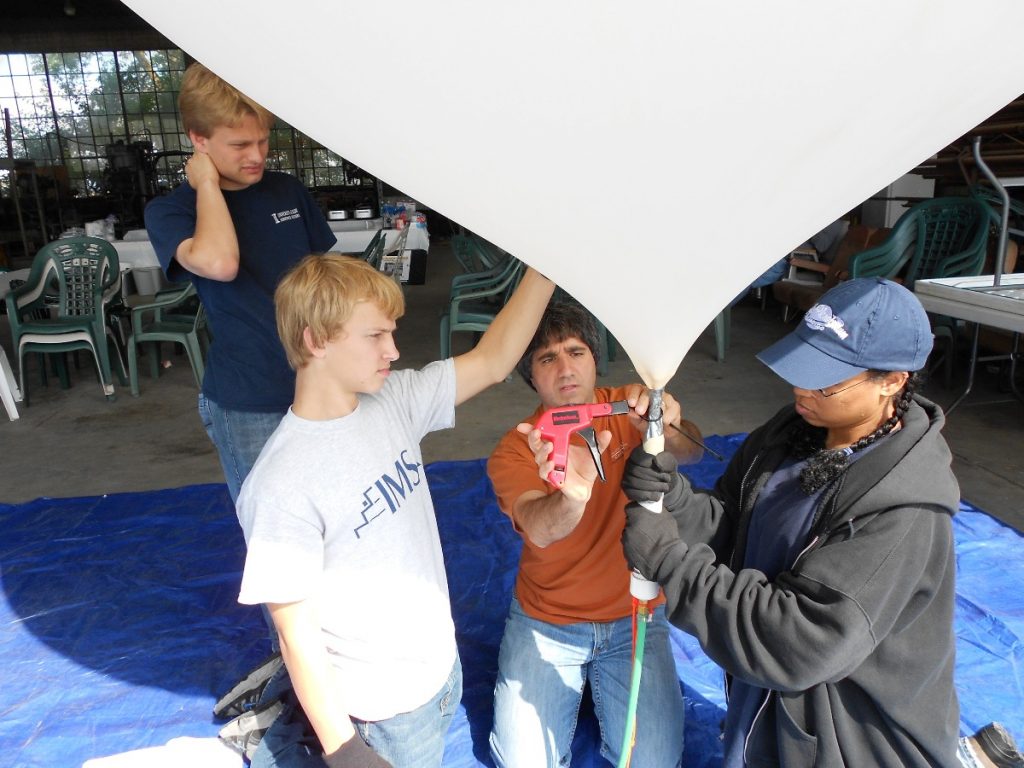

A decade ago, Spencer Gore was a teen intern at the Adler, where he spent summer days designing a stabilization system for the cameras that fly on Far Horizons flights.

On the long bus rides back to Union Station, he would dream up fantastical feats of engineering with Adler astronomer Geza Gyuk. Could you control the weather with a solar-powered reflector balloon? Or use it to power a city? No matter how bonkers an idea seemed, Geza would help Spencer break it down into smaller, more familiar physics problems. In 45 minutes, their questions would shift from Is this even theoretically possible? to Why hasn’t anyone tried this yet?

“By the end,” Spencer told me, “Geza would just leave me with it and say, ‘Okay, you can do it, but I want five percent.’”

Today, Spencer is the founder and CEO of a company called Impossible Aerospace, and the actual engineering challenge he’s set for himself is only slightly less ambitious than building a fleet of solar-powered reflector balloons that control the weather: to design a battery powerful enough to fly an airplane a long distance, make it commercially viable, and put a sizable dent in global carbon emissions in the decades to come.

In what felt like a reprise of one of those bus rides to Union Station, Spencer called me from inside a moving vehicle—a car he was driving through a Manhattan traffic jam—to talk about his work.

Most people, he said, think battery-powered commercial flights are impossible because jet fuel packs so much more energy per pound than batteries. If you replaced a tank of jet fuel with batteries that would last just as long, the batteries would weigh 40 times as much as the fuel, and the plane would be too heavy to fly.

Over the clicking of his turn signal and the honking of nearby car horns, Spencer turned the problem on its head: What if, instead of loading an existing plane with batteries, you could build a plane that was, itself, a battery?

“If you take a lithium-ion battery cell—a good one—and then you shaped it like an airplane, and then you gave it an electric propulsion system—so, a motor and a propeller—that were both as efficient as motors and propellers are today, how far could that lithium-ion battery fly itself?”

To answer that question, Spencer based his calculations on existing technology rather than hypothetical future batteries, motors, or propellers that might be more efficient. That’s a reflection of an important lesson he said he took away from his internship with Far Horizons—that there’s a lot one person or a small group of people can do with equipment you can buy off the shelf. You don’t need to be the CEO of your own company to push the limits of what’s possible.

So how far did he calculate that plane-shaped battery could fly itself? About 2,000 miles—enough to get you from Chicago to San Francisco with more than a hundred miles to spare.

In case you’re wondering if it’s even possible to build a flying battery, don’t worry: It is. Impossible Aerospace has already built a two-foot-wide drone called the Impossible US-1—essentially a drone-shaped battery—to get their big idea off the ground.

Before I hung up the phone and left Spencer to deal with the traffic, I asked him if anything else from his Adler experience informed the way he works now.

“Never discount the value of internships,” he said. “It’s good for the company because it brings a lot of energy. It’s also by far the best way to pay it forward, to educate and inspire the next generation. It’s the only reason that I got my start.”