How Many People Does it Take to Discover a Planet?

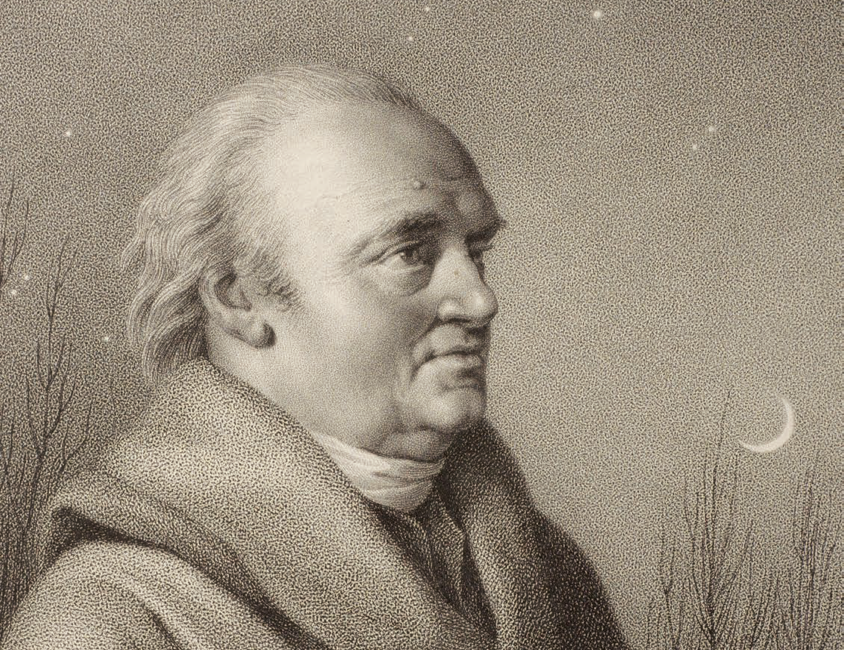

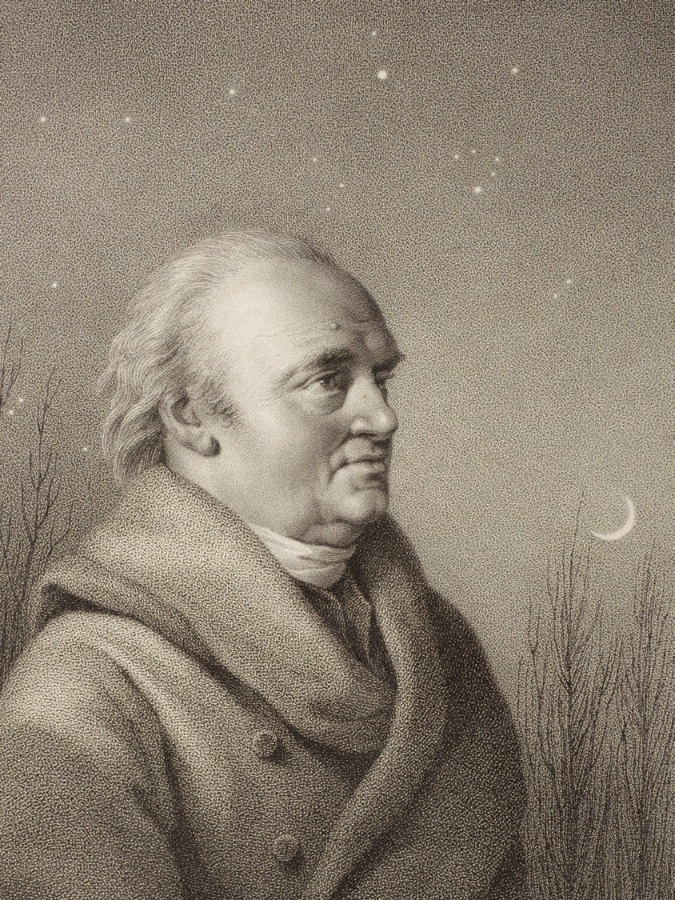

The evening of March 13, 1781, William Herschel was observing the sky with a fine 7-foot refracting telescope he’d made by himself, from the backyard of his home in Bath, England. At that time, Herschel was earning his bread as a musician, but he had been developing a strong interest in astronomy, sacrificing many of his rest hours in order to devour books on the subject and build telescopes.

While probing the area around the star Zeta in the constellation of Taurus, Herschel noticed the presence of an unusual star. Stars should in theory appear as points of light when seen through a telescope, but this one seemed to have a visible size. What Herschel had stumbled upon was no less than the planet Uranus. While Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn can be seen with the unaided eye (provided they are above the horizon, the sky is clear, and observers know where to look), Uranus will normally require a telescope to discern it among the stars. Herschel thus became the first person to discover a planet since antiquity.

At least, this is a nice way of telling the story, even if overly simplistic. First and foremost, how did Herschel himself react to what he saw through his telescope? To begin, it was necessary to check if the object was moving against the starry background. Herschel was able to confirm that just four days later, with new observations. Still, he did not promptly assume that the moving object was a planet. In fact, he initially described it as being either a “nebulous star” or a comet, leaning toward the latter.

Herschel had been establishing good relations among the English scientific community of his time, and did not take long to share the news about the unusual object with other astronomers. However, at the time Herschel was just an amateur astronomer getting started, and his lack of experience showed.

Not that there were that many astronomers by then who would qualify as professionals, but Thomas Hornsby at Oxford and the Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne at Greenwich were certainly part of that select group. The two seasoned astronomers immediately asked for the coordinates of the object, in order to keep track of it themselves. But Herschel could only provide an approximate description of its observed positions in the sky.

It is true that it was Herschel who started the process that led to its identification as a planet. But as shown above, its discovery was much less a sudden, momentous feat of one individual than a gradual process involving several other people.

Besides, the anomalous appearance of the object was more evident through Herschel’s own telescope, which further contributed to Hornsby and Maskelyne (especially the former) taking pains before they could finally track it down after weeks searching. Hornsby initially supported the idea that it was a comet, whereas Maskelyne posited it was either a comet or a planet. It was only by the summer of 1781 that, using precise observations amassed by these and other experienced astronomers, mathematicians were able to compute the orbit of the object and confirm that it was, in fact, a planet.

Following the advice of Joseph Banks, one of the leading figures of British science at the time, Herschel named the new planet Georgium Sidus as homage to King George III, which granted him the king’s patronage and allowed Herschel to concentrate on astronomy and telescope making for the rest of his life. In continental Europe, and especially France, the planet was known as Herschel before it was finally christened Uranus, following the old tradition of naming planets after the gods of classic mythology.

Interestingly, Uranus had already been included in star catalogs before Herschel observed it, but just as another star. It is true that it was Herschel who started the process that led to its identification as a planet. But as shown above, its discovery was much less a sudden, momentous feat of one individual than a gradual process involving several other people. We may continue to celebrate Herschel as the first person to ever discover a planet since antiquity, but we should not forget that the discovery was not only his. This caveat applies to whatever scientific discovery, astronomical or otherwise, we may choose to focus on.

What we call scientific discovery is usually a process that unfolds in time, not a single “Eureka!” moment, and the “discoverer” is almost always a group of people, regardless of who started or led the process, or who was better or luckier at getting credit for it.