Meet Maude Bennot: The Woman Behind the Adler

The story of Maude Bennot—at least, the part of it that concerns the Adler Planetarium—doesn’t have a great ending. This is just a heads-up: You won’t like what happens. But if you love science and community and the place the Adler is today, you will like Maude Bennot. You’ll like her so much that you’ll find her story worth reading until the very last word.

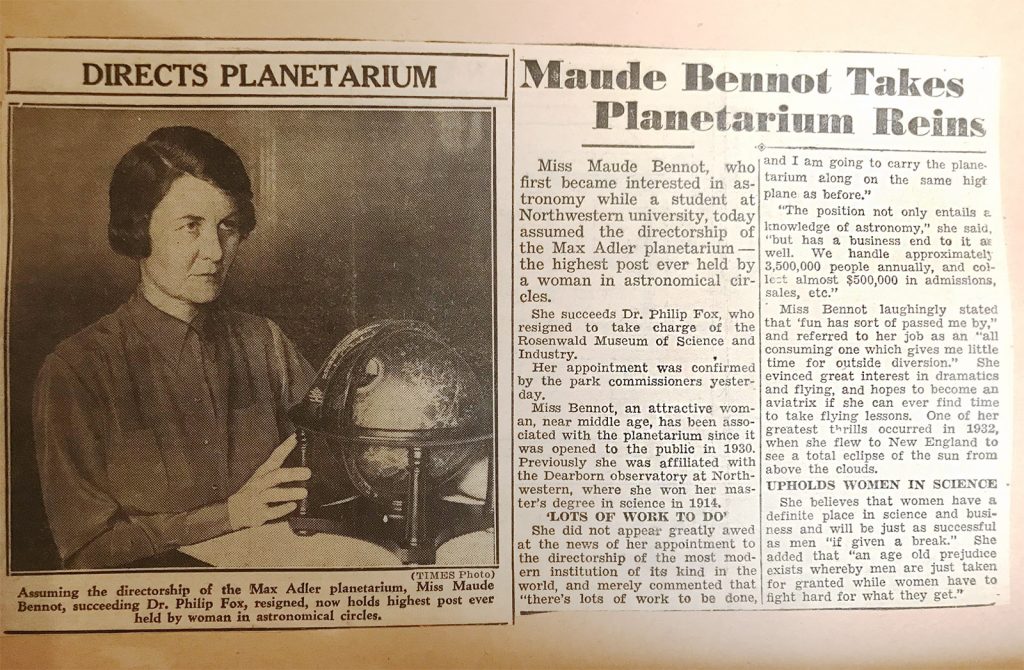

Maude was the director of the Adler Planetarium from 1937 to 1945. She was the second director of the Adler and the first woman in the world to run a planetarium (or, as far as we know, any science museum).

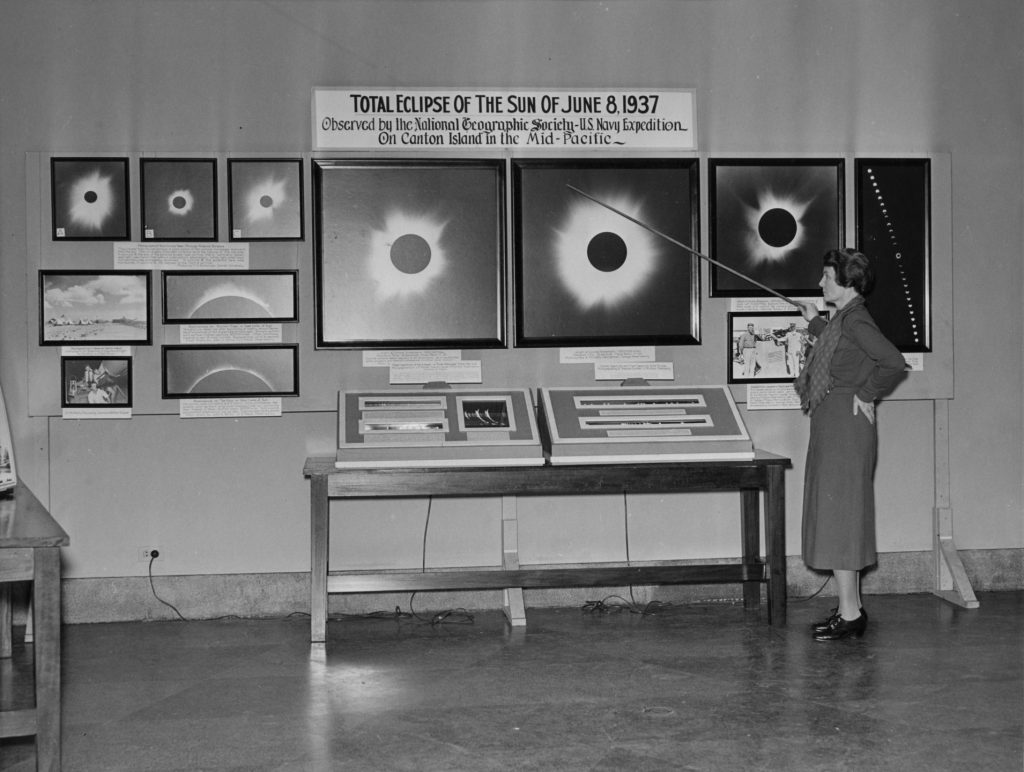

Even though being the first woman to do something few men were qualified to do was a massive accomplishment, it feels limiting to focus on her gender like that. In fact, based on everything I’ve read about her, my guess is that she’d hate it. While it does end up being deeply relevant to the story of how she got to the Adler, her life here, and the circumstances under which she left, the fact that Maude was a woman is one of the least interesting things about her. She graduated valedictorian of her high school at age 16, took pilot lessons, and played the violin.

But we do have to talk about gender because, for Maude, there was no escaping it. Everywhere she went, she ran into descriptions of herself like this one from the (male) journalist Sydney J. Harris in the Chicago Daily News:

“As the only woman director of a planetarium in the country—and possibly in the world—Miss Bennot has had a grim struggle to attain, and to keep, her unique position. Park District officials, who operate the museum, were skeptical of this slim, fragile woman. Masculine astronomers shook their heads dolefully, said she was more in place in a tearoom than in an observatory. Today, they have chewed those words into very tiny bits.”

I found that story in a scrapbook of press clippings about Maude in the Adler’s collection. The newsprint is a yellowish brown and the thick, brittle, three-hole-punched scrapbook pages are no longer bound together. It’s more scrap

The clips tell the story of an undergraduate at Northwestern University who happened to get a part-time job doing administrative work for the director of the Dearborn Observatory—a man named Philip Fox—only to discover that she was fascinated by the cosmos. She would return to the observatory years later, as a graduate student in astronomy, to teach new stargazers what she had learned.

When local businessman Max Adler asked Philip Fox to be the first director of his new planetarium in 1929, Philip said yes on one condition: that Maude could be his (paid) research assistant. At the time, there was no way anyone in the astronomy community would have hired Maude for such a plum position without an advocate like Philip. It was a different (and vastly more sexist) time—just nine years after American women had won the right to vote.

It’s all in there, in bits and pieces, in the scrapbook. When Philip leaves the Adler in 1937, World War II is in full swing, men are scarce, and even if there were more of them around, the vast majority of them wouldn’t know what to do with a planetarium—the Adler was one of just a handful planetariums in the United States at this point, so almost no one had the resume for it. No one except Maude Bennot. So Philip passes the torch to her. And here, the tone of the story shifts.

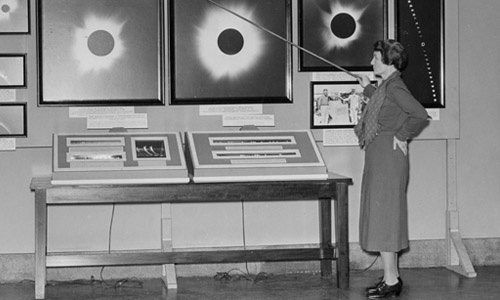

Long, feature-y newspaper profiles describe a quiet woman with a steely backbone, someone so accomplished and so well suited to her work that she doesn’t even seem to care that she isn’t married. An incredibly awkward photo shows her standing behind a flowery potted plant, holding a sundial, with a look on her face that says, “Flowers? Really?” A columnist drops a foreboding hint that the Chicago Park District—which has the final say in museum staffing decisions at the time—is angling to replace Maude with a man. The Park District also never formally recognizes Maude as director. They pay her the same salary she earned as Philip’s full-time research assistant—about two-thirds rate they offered Philip—and she is not permitted to hire an assistant of her own.

Meanwhile, Maude is busy creating the Adler we know and love. Maude IS the Adler—and not just in the sense that she runs the projectors, gives the lectures, writes the budgets, pays the bills, and answers the phones. She’s the Adler in spirit, too. She is smart, hardworking, generous with her time. Always eager to bring the joy of exploring the Universe to new people of all ages and backgrounds, no matter what brought them in the door, and ready to show everyone—soldiers, students, journalists, even people who just need help solving an astronomy clue in the daily crossword—the practical benefits of looking up.

Today, the Adler is fully staffed with people who, like Maude, would happily drop whatever they are doing to draw you a diagram or share a favorite mind-blowing fact about the Universe with you. It’s easy to imagine her here, walking the halls, placing orders, picking new topics for her monthly lectures, being mistaken for her own secretary.

In 1945, that columnist’s ominous prediction came true: Maude was fired by the Park District, allegedly for “insubordination”—a failure to follow orders—and a less-qualified man was waiting in the wings to replace her.

And then, quite suddenly, Maude disappears from the records. At the age of 62, she leaves the Adler, furious, and (according to one historian) she quits astronomy for good. This is the ending I warned you about. But it wasn’t really the end. The story goes dark until Maude’s death at age 90, but because there are no more breathless profiles about this walking anomaly, the brilliant delicate fiercely independent flower who created our community from scratch, we don’t know what she did with those three decades. Maybe she spent them flying around the world like Amelia Earhart or playing first fiddle in a string quartet. Whatever happened, wherever she went, pieces of her will always be here at the Adler. A scrapbook and a scrappy spirit. A way of meeting people where they are, taking their hands, lifting their gaze to the sky, and showing them who they could be.