Tunguska: Unraveling the Mystery

Setting: Tuesday, June 30, 1908, around 7:15 am. A remote forest near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in Siberia.

A large fireball streaks through the sky followed by an intense wave of heat felt up to 40 miles away. A loud explosion. The ground shakes. Silence.

If the playwrights of today were to write a theatrical piece about the mysterious event that took place 111 years ago in remote Russia, its introduction would look something like the above. A rather bold, dramatic scene set for something that would become a century-long debate. The event near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River was unexplainable by locals—or rather the multiple accounts of the incident didn’t always add up. Some people saw an explosion. Others only felt tremors or heard an explosion. Indigenous peoples to the area (the Evenkis and Yakuts) even believed a god had sent the fireball to destroy the world.

Following the occurrence, Russian newspapers would report the event as a possible meteorite impact. Over the decades, others would hypothesize a volcanic eruption of some kind. In the 1970s, American physicists would propose the phenomena as a small black hole colliding with Earth. Whatever it was, as many as three casualties were reported in the area. And it’s thought that there was up to 30 individuals in the blast zone. It is unclear how many of them may have survived.

Due to the remoteness of the region, as well as the political situation of the time (the Russian Revolution and the outbreak of WWI), scientific investigation at the potential site of impact was delayed for nearly 20 years, leaving a lot of room for speculation.

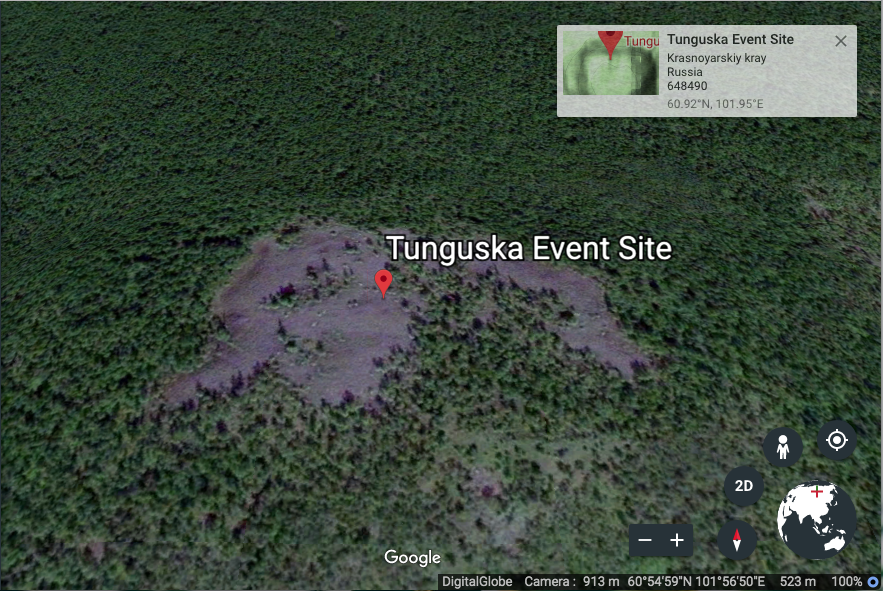

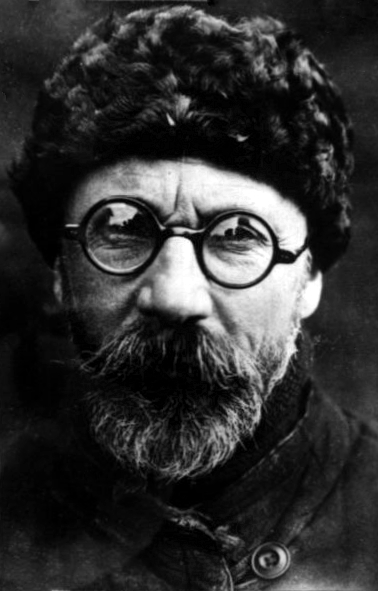

Leonid Alekseyevich Kulik of the Russian Meteorological Institute would eventually become interested in the area. In 1927, he would send an expedition team to the site with the hope of finding meteorite fragments and materials. They would discover that the area impacted by the event would cover approximately 800 square miles. One of the most peculiar things found by Kulik and his team was at “ground zero” where they expected to find a large impact crater. Instead of a massive hole, the team would discover a five square mile zone with scorched trees devoid of branches, standing upright in a pattern pointing away from the center.

In the end, Kulik’s team would come up short on their search for meteoritic fragments.

Ultimately, scientists and historians have come to conclude that, despite the lack of meteoritic material found in the area, the probable cause of the Tunguska Event (as it has come to be known) was indeed a meteorite impact. Likely from an asteroid that was originally 40-80 meters in size.

But how do we know? Many of the anecdotal accounts of the incident, as well as the supporting evidence from the butterfly-shaped blast pattern at the impact site, help support this conclusion.

“In the 1960s, the Soviets experimented recreating the blast site by sliding explosives down a wire into mini model forests,” explains Adler astronomer Mark Hammergren.

The experiments suggested that the hypothesized meteorite approached the Tunguska site at an angle of roughly 30 degrees from the ground and 115 degrees from north, and likely exploded in mid air. This would also help explain why a large impact crater was never discovered at the site.

Small meteors enter and burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere every single day, never coming near to having impact with the ground. Scenarios like the Tunguska Event are much rarer. It is estimated that they occur every 300 to 1,000 years.

Today, scientists have found and mapped the course of approximately 97% of asteroids bigger than 1 km in our Solar System. These are the asteroids that could wipe out entire cities. They’ve also cataloged the course of virtually all asteroids that are bigger than 5 km in diameter (in other words, asteroids that are sizable enough to destroy civilization as we know it). The good news is that none of these existence-threatening asteroids are on a collision course with Earth!

We don’t know when the next Tunguska-like event will be. However, it’s likely that with advances in today’s technology, and the number of astronomical surveys happening across the globe, whenever that day comes, we will have enough warning to be able to evacuate any threatened areas that are populated with people. And humanity will continue on, business as usual.

Header Photo: View of the Tunguska Event impact site as seen on Google Earth.